Kyle's statement of purpose appeared on the cover heading to the first issue of Graphic Story World. His fanzine offered a potpourri of comics related news and articles from the very start; a stark contrast from the majority of publications that focused almost entirely on superheroes and the current Marvel and DC offerings.

Kyle's twelve page newsletter packed a lot into its first issue. Along with news from the mainstream comic book publishers, with particular emphasis on Jack Kirby's current DC endeavors, Kyle included information on the latest conventions, fanzines, undergrounds (which were unencumbered by Comics Code restrictions since they were not sold through traditional outlets), foreign publications, animation and a column on Gil Kane's Blackmark illustrated novel by noted interviewer and author John Benson.

Kyle's editorial on the back page emphasizes his interest in comics as an international art form. From the start Kyle saw the medium's unlimited potential. As early as 1963 he came up with the phrase "graphic story" and "graphic novel" as a means of expressing a larger canvas. It would take a decade or two, but his expression was eventually adopted into the language of comic book fans and publishers. Today authors writing articles about the business employ the terminology and bookstores often have a "graphic novel" section.

Graphic Story World # 3, October 1971, Jim Jones cover art. With it's third issue Kyle expanded GSM from twelve to sixteen pages. In his editorial he explained "There's just too much happening in the graphic story world to be covered adequately by a twelve page magazine." Those extra pages were filled by a new column, Graphic Story Review, focusing on a variety of comic related books commented on by a host of authors, including Kyle, and an article by Fred Patten on the french humor strip, "Asterisk."

Yesteryear: Whatever Happened to..?, authored by Hames Ware, originally began as a small column in the first issue. A particular favorite, Ware tracked down many largely forgotten artists of the golden age era, updating fans on their current activities (many had left the business). Ware had the distinct ability to identify artist's styles and was instrumental in giving them recognition and credit. Ware co-edited Jerry Bails' invaluable Who's Who in American Comic Books, now available as an online resource: http://bailsprojects.com/whoswho.aspx

GSW # 4 (December 1971) was the last issue to be labeled a newsletter. In just two months Kyle added an additional ten pages. Clearly, he needed more room to cover all his interests in the world of comics. This issue introduced a new column on comic strips by Shel Dorf and expanded its international, news and review sections.

Graphic Story World # 6 (July 1972), was eight pages shorter than the previous issue, but didn't lack for content. In addition to the regular columns, artist Dan Spiegle was interviewed. A distinguished craftsman, Spiegle's comic book work for Dell/Western's TV/Movie related titles didn't get much coverage in the fan press. In the "Round Table" letters section artist Fred Guardineer, who had been the focus of an earlier article by Hames Ware, updated fans on his present activities. On a personal note, many years later the name Fred Guardineer came up in a conversation with my Uncle Joe. Aware of my interest in comics, one day he mentioned that a guy he worked with in the Babylon, Long Island branch of the post office used to draw comics. His name: Fred Guardineer. Sometimes it IS a small world.

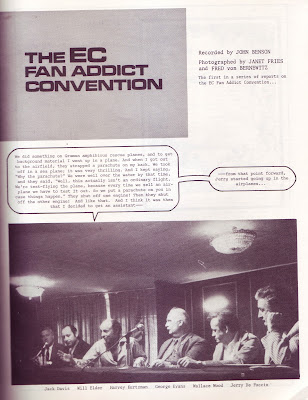

Every issue of GSM had plenty of convention coverage. In addition to the EC Fan Addict Con, there were reports on the New York Comic Art Convention, San Diego's Con and the first (and last?) American International Congress of Comics, which took place in New York and included a mix of European and American artists, organized by the National Cartoonists Society.

Graphic Story World # 8, (December 1972). Kyle's editorial in this issue explained that the magazine would soon separate into two distinct publications. New features included "The Wonderworld Forum", which addressed comments from fans and pros on all aspects of comics, and the first - and last - column by prolific fan Tony Isabella, reporting on upcoming releases from Marvel, DC and Skywald. Recently hired to work as an editorial assistant for Marvel, Isabella had to bow out. He would go on to write and create features for Marvel (Captain America, Ghost Rider, Iron Fist), DC (Black Lightning) and other companies in the decades ahead.

Issue number 9, now re-titled Wonderworld (August 1973), incorporated further changes. In his editorial Kyle explained that the magazine would henceforth consist of graphic stories (represented by "Penn and Chris", an adventure strip by Dan Spiegle and "The Victims", a French translated story) alongside the usual features and columns. Kyle noted that the magazine was selling well on newsstands; in itself surprising, since fanzines were almost exclusively bought through mail order subscriptions and the handful of stores that specialized in comics at the time. The move from a bi-monthly to quarterly schedule was announced, as was the upcoming publication of Graphic Story Quarterly, described as:

"America's first professional magazine devoted to all aspects of the graphic story - comic books, newspaper strips, underground comix, the growing field of magazine strips, hardcover books and paperbound editions, the international graphic story, yesterday's comics world - and tomorrow's."

This, in addition to a Graphic Novel by George Metzger, Beyond Time and Again, and another new title, Quest, "the world's first graphic story magazine for the mature reader.."

Kyle's focus in Graphic Story World/Wonderworld had been expanding from issue to issue, starting out as a discussion on comic art content to inclusion of graphic stories.

His future plans pointed to new, extremely ambitious directions, and an argument could be made that he was overreaching by attempting to fit too many ingredients under one title. Perhaps these problems would have been resolved with time.

Unfortunately it is a question that will remain unanswered.

Wonderworld # 10 (November 1973) was the final issue. It included a variety of features, from Max Allan Collins' article on Mickey Spillane's comic book background to Mark Evanier's report on the 1973 New York Comic Art Convention, along with art and stories by Jack Davis, Dan Spiegle and unpublished work by master artist Alex Toth (some strips and features promised in the previous month's editorial were either truncated or failed to appear). The promise of future issues and new publications (Graphic Story Quarterly and Quest) was not to be realized, but Kyle did publish George Metzger's Beyond Time and Again, perhaps the first book of its kind to be labeled a "Graphic Novel", in 1976.

What went wrong? According to Kyle GSM/Wonderworld was selling well. In Bill Schelly's book, The Golden Age of Comics Fandom, Kyle gave his view of the magazine:

"It was deliberately somewhat over-serious in tone, as I - a little heavy-handedly, I think - tried to bring comics criticism into the literary mainstream. When my entire subscription list was destroyed in a flood, I discontinued publishing. Illness in my family made it too costly to begin again."

This author would argue that Kyle's fanzine/magazine was far from ponderous, particularly before it grew to encompass graphic stories. A publication that distinguished itself, focusing on all aspects of comics - as the early issues did - alongside a separate publication for graphic stories might have worked out better. Nevertheless, Kyle's ambition is to be admired. He produced an intelligent magazine that was informative, attractive and diverse. Kyle left the world of fanzines and went into business as the owner of a bookstore in California. In 1983 Kyle commissioned Jack Kirby, an artist he greatly admired, to produce an autobiographical story. "Street Code" did not see publication, though, until 1990, when Kyle briefly revived Argosy magazine. The story appeared in its second issue.

Richard Kyle passed away on December 10, 2016 at the age of 86. His legacy lives on in the superior work he left behind.