Since the earliest days of the industry, when most comics cost 10 cents, publishers experimented with different formats and prices. In 1939 National (later know as DC) published New York World' s Fair Comics, a tie-in to the famous event that took place in Flushing, Queens that same year. Priced at 15 cents with 96 pages of content, it resurfaced as World's Best Comics # 1 (spring 1941), starring popular characters Superman and Batman alongside an assortment of other costumed heroes. The title was tweaked to World's Finest Comics, retaining the same price, although the page count was cut to 72 (and later 64) pages, until 1954 when it reverted to standard size.

Clocking in at 100 pages, Fawcett's premiere issue of America's Greatest Comics was on newsstands circa 1941. One of DC's biggest competitors, their Captain Marvel even outsold Superman for a period of time. Mac Raboy cover art. Other publishers took note of DC's success, particularly Fawcett with America's Greatest Comics, starring top-seller Captain Marvel, joined by Spy Smasher, Bulletman and various second-tier protagonists. Another heavy-hitter, MLJ, originally focused its attention on superhero fare, but the character of Archie Andrews surpassed expectations and soon became their primary focus, so much so that the company was eventually rebranded as "Archie Comic Publications." An array of 25-centers starring Archie and his teenage gang followed. While these comics sold at various times during the year, the summer months were often a period when extra titles proliferated; in all likelihood maximum sales were attained due to many youngsters being out of school.

Fall 1949 saw the debut of Archie's first Annual. At a whopping 116 pages this comic must have been a boon to parents going for long car rides with their children! Bob Montana cover art.

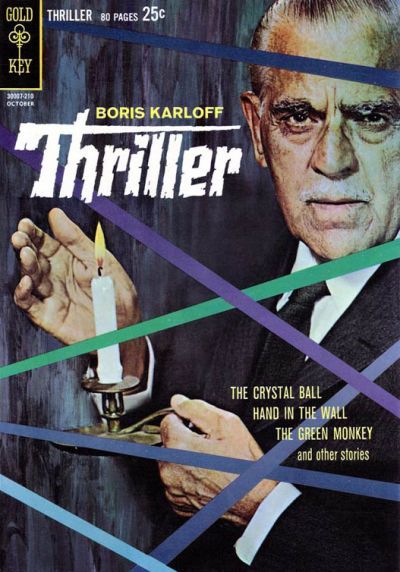

Boris Karloff's Thriller was based on the anthology TV show of the same name. This 80 page comic was available on newsstands sometime around July, 1962, and included stories by Leo Dorfman and art by Mike Sekowsky, Ray Bailey, Tom Gill, Alberto Giolotti, Giovanni Ticci and Jerry Robinson. To mimic a phrase host Karloff began each show with: "As sure as my name is Nick Caputo, I can assure you this post is a Thriller!"

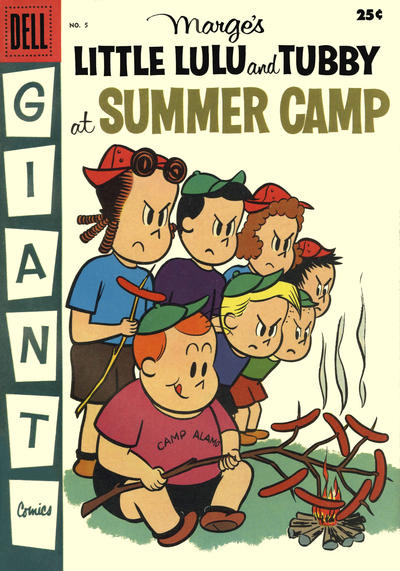

Dell's Little Lulu was a tremendous success headlined by author John Stanley, who had an affinity for writing about children from their point of view. Cover art by Irving Tripp. Marge's Little Lulu and Tubby at Summer Camp # 5, July 1957.

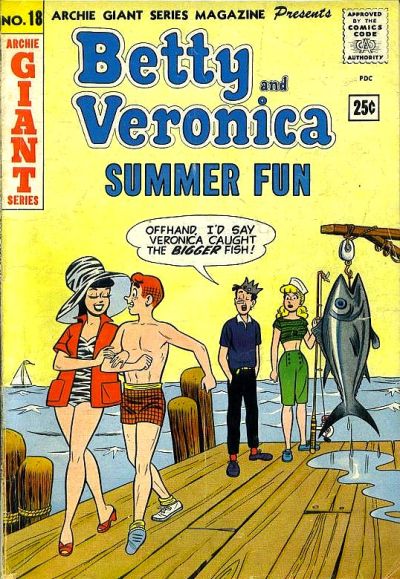

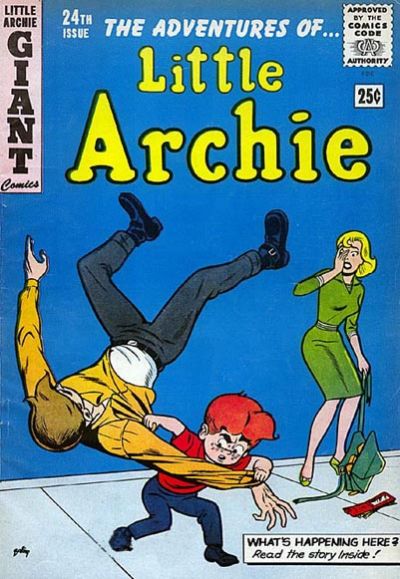

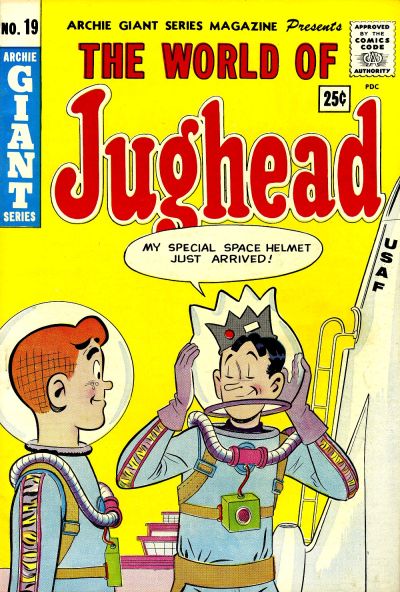

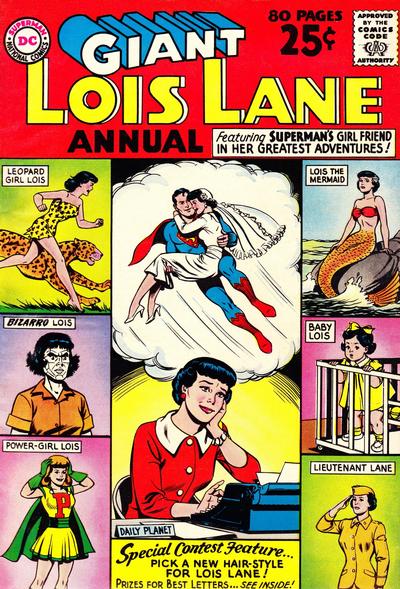

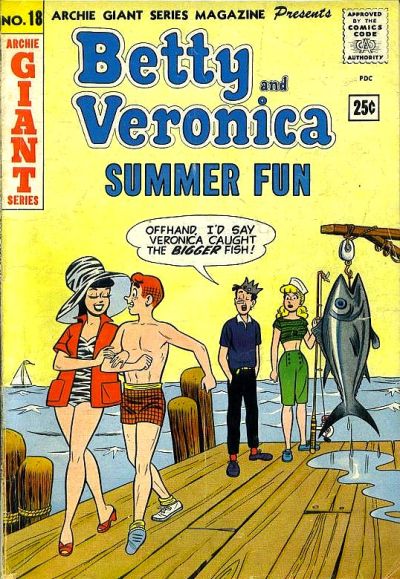

DC had success with their 80 page Annuals many of which featured reprinted stories. Cover art by Sheldon Moldoff, Dick Sprang and Curt Swan; inks by Charles Paris, lettering by Ira Schnapp. Batman Annual # 1, June, 1961. By 1961 National/DC focused much of their attention on superhero-related content. This led to them crafting 25 cent versions of Superman, Batman, the Flash and Justice League of America, selecting contents from their archives. Archie publications, another powerhouse in the field, published The World of Jughead, Betty and Veronica Summer Fun, Little Archie and Madhouse. Western also embraced the trend with a huge selection of titles such as Hanna Barbera Summer Fun, Popeye, Little Lulu and Boris Karloff's Thriller. Harvey included extra-length presentations of their most successful comics such as Richie Rich, Sad Sack, Little Audrey, Spooky, Little Dot and Blondie.

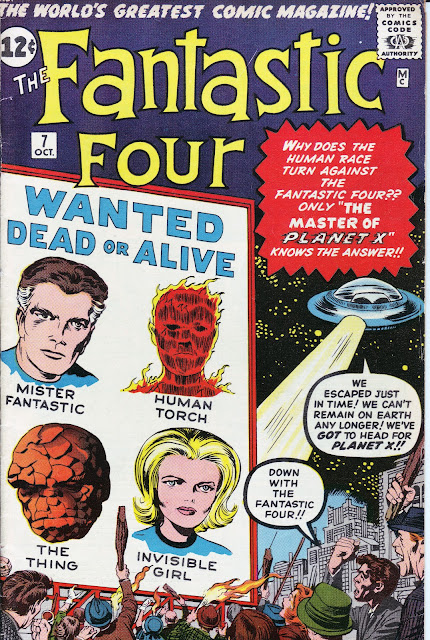

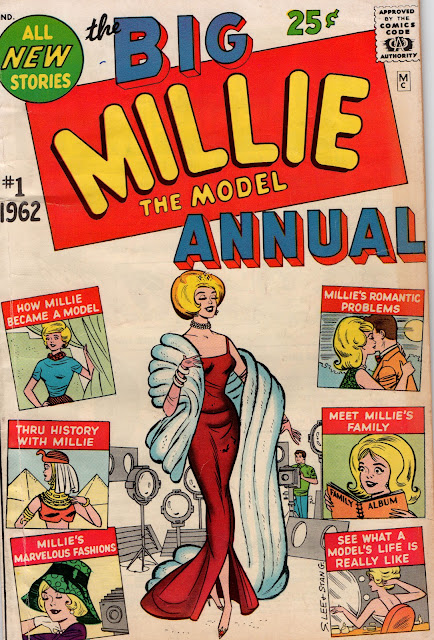

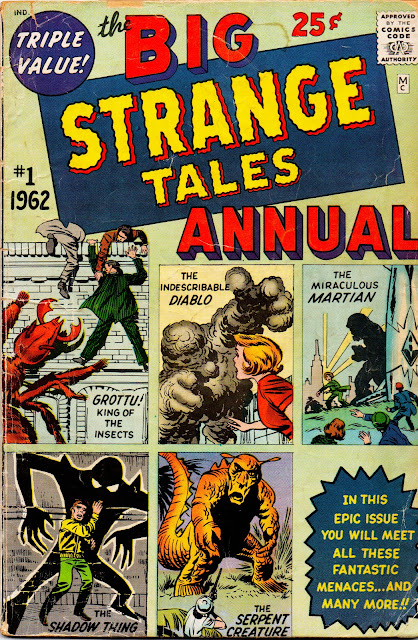

The comics spotlighted below filled the nation's newsstands in the summer of 1962, offering hours of entertainment for children trekking to the beach or going for long rides on vacation. Into the mix came the beginning of Marvel's Annuals.

Millie the Model Annual # 1. Pencils (and likely colors) by Stan Goldberg; inks by Sol Brodsky; lettering by Artie Simek.

That same summer Martin Goodman, publisher of Timely-Atlas (soon to become known as Marvel), aware of his competitor's profitability with higher-priced comics, tasked editor Stan Lee to follow their lead.

It may have been Goodman's decision in choosing what titles to publish, based on sales of their ongoing series. Millie the Model, which began in 1945, was an obvious choice, since the character was extremely popular, appearing in her monthly comic book and Life With Millie. This Annual was the first to include all-new material, written and drawn by the regular team of Stan Lee and Stan Goldberg.

Stan Lee was known to ask his audience for input - but it didn't start in the superhero titles - as this page reflects. Lee promoted both himself and artist Stan Goldberg on this feature page. He would continue that practice throughout the Marvel line.

While cross-promotion became prominent during the Marvel superhero expansion, evidence points to Lee always being inclined to move in that direction, likely inspired by radio programs such as The Jack Benny and Fred Allen Shows, where the comedians had a running "feud" and supporting characters were often referenced or interacted with each other.

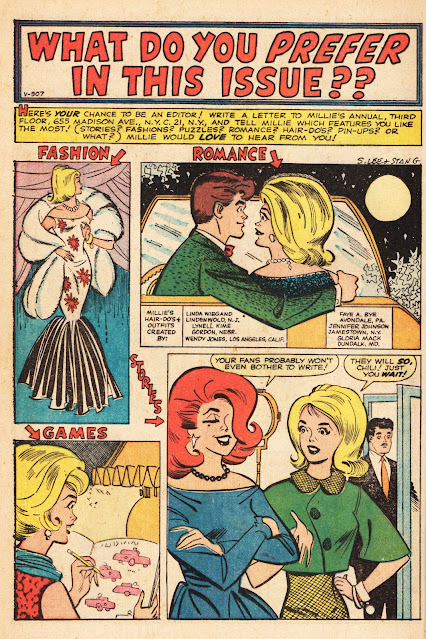

One month before Millie was in candy stores rival DC comics debuted Lois Lane Annual # 1 (June 1962). It starred the feisty reporter who was recognizable to fans of both Superman comics and the TV show. Her core audience was likely young girls, a demographic that overlapped with Millie's buyers. Cover by Kurt Schaffenberger; lettering by Ira Schnapp. As an aside, I discovered the cover of this Annual on the floor of a closet in my house; an early childhood memory I've retained all these years later. The other title Marvel chose for extra-length treatment was Strange Tales, an ongoing anthology series in publication since 1952, originally consisting of horror material, but toned down to lighter fantasy fare when the Comics Code came into effect, and finally settled into monster-oriented stories in the early 1960s.

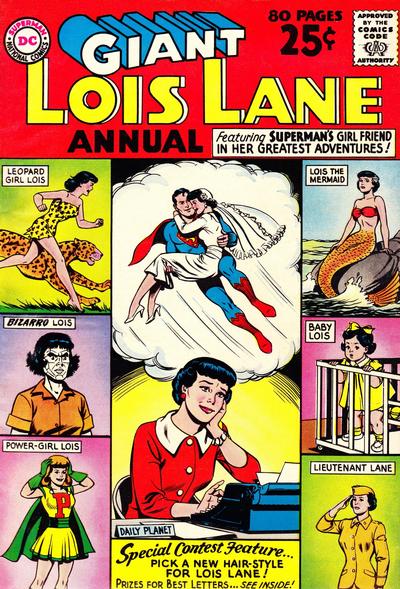

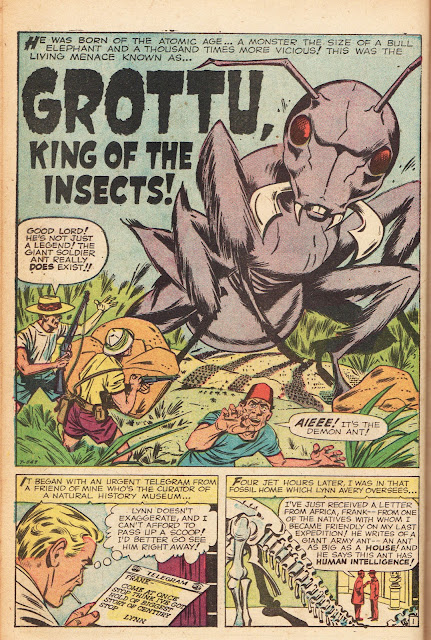

Strange Tales Annual # 1 was on stands the same day as Millie, although it differed in that it consisted of material published just 2-3 years earlier. Jack Kirby pencils and inks (along with a touch of Dick Ayers; see the following caption); Artie Simek letters and (likely) Stan Goldberg colors.

This was Kirby's original cover to Strange Tales Annual # 1. Stan Lee obviously felt the monsters needed to be menacing humans, so he instructed Kirby to revise each scenario. It was probably rushed out in the office; Kirby's pencils and inks on the second version being a telltale clue. Since I love minutia I noticed that the bottom right "Shadow Thing" figure and background were utilized (and slightly repositioned) with Kirby adding the fearful citizen, so a trace of Dick Ayers' inking can be seen on the published cover.

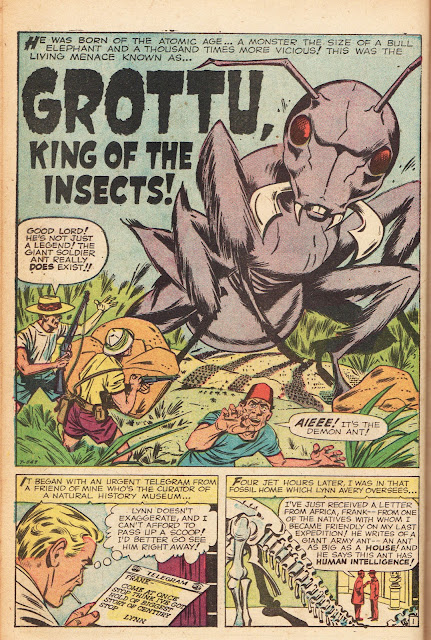

As noted, all the stories were reprints from the monster titles. Grottu originally appeared in Strange Tales #73, February, 1960. Plot likely by Stan Lee; Script likely by Larry Lieber; Jack Kirby pencils; Bill Everett inks; Artie Simek letters and Stan Goldberg the likely suspect as colorist.

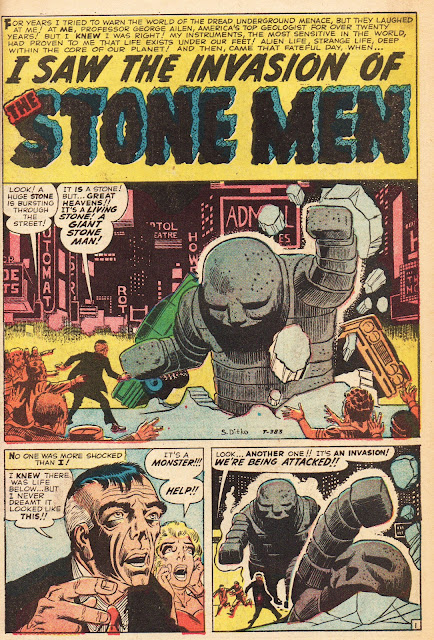

Originally from Tales to Astonish # 6, November 1959. Steve Ditko art; Artie Simek letters; Stan Goldberg colors (?). Writer unknown.

"I Saw the Serpent that Saved the World!" originally presented in Journey into Mystery # 55, November 1959. Possible Lee plot; Lieber script; Don Heck pencils and inks; Artie Simek letters and Stan Goldberg colors (I think!)

Strange Tales Annual # 1 included monster/fantasy/sci-fi stories by two of their top artists (Kirby and Ditko; each represented by four stories) closely followed by the talented Don Heck (three) along with solo outings by John Forte and Paul Reinman. It was a fine sampling of their monthly output.

Popeye and his cast of characters occupy this impressive cover by Bud Sagendorf, who wrote and drew all the interior stories. This was the first issue published by Western (aka Gold Key) with the numbering continued from Dell's series. Popeye # 66, July 1962.

Western had the rights to many animated cartoons, including Warner Brothers, Hanna-Barbera and Jay Ward. They produced giants for many of them during the summer, including Bugs Bunny, Yogi Bear, Huckleberry Hound and Terrytoons. This attractive cover is attributed to Pete Alvarado and Norm McGary.

Harvey specialized in comics for the small-fry, as the above trio of titles reflect, all of which were on sale during June-July of 1962. Sad Sack cover by George Baker, Richie Rich is uncertain and Casper is by Warren Kremer.

Harvey produced one giant-sized adventure book in 1962, Black Cat, a character that dated back to 1942. Lee Elias cover art; Joe Rosen lettering. Interior stories were reprints drawn by Elias, with some scripted by Bob Haney. In later years Harvey's Giant's spotlighted Will Eisner's Spirit and Simon and Kirby's Fighting American.

Archie Giant Series # 18: Betty and Veronica Summer Fun. Pencils by Dan DeCarlo; inks by Rudy Lapick. On sale in July, 1962.

The Adventures of Little Archie # 24. Bob Bolling art and lettering; Victor Gorelick colors. Interior stories and art by Bolling; Joe Edwards, Joe Harold and Dexter Taylor. You could have purchased this comic in August, 1962.

I'd be remiss if I skipped over my favorite character, Jughead, who predated Kramer by half a century or so! Archie Giant Series # 19: The World of Jughead; Samm Schwartz art. If you could time travel back to the late summer of 1962 this comic would be available at your local candy store.

Archie and his teenage pals were hugely successful, with their popularity overlapping on radio, television, music and animation.

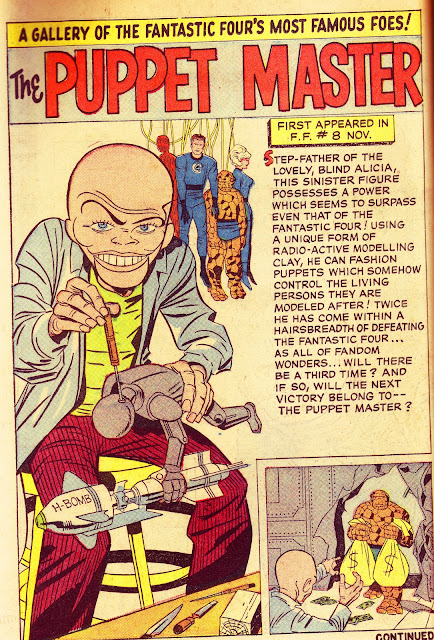

The 1962 Annuals/Giants consisted of an assortment of subject matter, although, as one can clearly see, the majority were mainly geared towards pre-teens. In that period humor, girl-oriented titles and cartoons, particularly the recognizable Saturday morning and afternoon syndicated programs, were extremely popular. Fantasy and superhero material were also gaining ground, and from 1963-68 Marvel often crafted new, longer stories and special features, the best arguably being the Lee-Kirby-Ditko Fantastic Four, Journey into Mystery/Thor and Amazing Spider-Man Annuals.

Since there has been much written about that period (including on this blog) I believe its important to look at the bigger picture and get a realistic perspective of what was selling 60 years ago. Mainstream comics were readily available in candy stores, newsstands, luncheonettes, railway stations and many other locations that kids, either on their own or with family, could easily access. Unfortunately, in the decades that followed, the audience for comic books decreased, with children being lured away by a veritable avalanche of diversionary entertainment options. The remaining audience is marginal and consists of many older hard-core superhero fans, or those interested in adult-oriented fare. Gone, for the most part, is the ability - or inclination - to reach out to younger readers. Thus, comics have become of interest primarily to the indoctrinated. Annuals, once a special presentation, produced with care, have been overtaken with superhero pyrotechnics, and such anthologies as Thriller are a thing of the past.

Looking at it from an adult perspective I can appreciate the quality of work that went into the various titles. Each company had its own distinct style and the material in general was well-crafted. Many Annuals sold in the hundreds of thousands. Even at Marvel during the superhero boom of the 1960s, Millie the Model remained a solid seller into the 1970s. That audience is largely gone now, and it's doubtful it will ever return. The present generation has many choices with new technology, and the world moves much faster than it did decades ago. Still, those days can be reflected on as a distinct period in time, when comics were truly a part of our popular culture.

There were GIANTS in those days! 96 pages worth! A charming baseball-oriented cover by Fred Ray, from World's Finest Comics # 3, Fall 1941